The back of the sky

When does a landscape become familiar?

This exhibition from Oluwasemilore Delano explores our bodily and immaterial attachment to landscape, the space between the ground and the sky. Through the cows depicted in ‘the back of the sky’, Delano documents an unconscious movement through space - their backs massive and heaving, their legs simultaneously imbued with power and gaunt. These beasts carry a sense of dominance in the landscape, yet also a sort of desolation; as known as the land is to them, their mindless grazing demonstrates no conception of familiarity.

“...the spine carries the weight.

Driving through Kaduna, The shadow of a tree on a bare concrete wall, Bovine Backs are gathered,

all travelling on red sand.

I look out the window, my mind taking notes of the sand, the unending landscape, flat, only with the sky as its boundary. The road leads to all places and nowhere at once. We pass by a herd of cows grazing on the side of the road. They are led by a small boy who can’t be more than twelve years old. He knows them well; he sits with them, staff in hand. The cows remain together, their spines arched downwards feeding, their ribs moving, thin skin pulled over muscle and bone, their backs remain fixed in place, unmoving, splitting the sky.

They are the land and the red of the sand.

The car drives on.”

There’s a kind of noncentrality to the works—a refusal of fixed location. What at first appears as a fragmented collection of forms gradually unfolds into something solid, stable, and interwoven. A surplus of narratives move in simultaneous conversation, expanding on the idea that multiple events, conditions, and times can coexist—each occupying its own space, yet leaning into one another.

This lack of location is not absence, but tension—a kind of restlessness within the act of self-referencing.

This speaks to Delano’s wider practice: the challenge of locating oneself while away from home, and the overlapping voices, memories, and instincts that travel with you. Within one life, there are many tenses in which we speak, many selves we create. How do we locate ourselves, and in what tense do we truly belong?

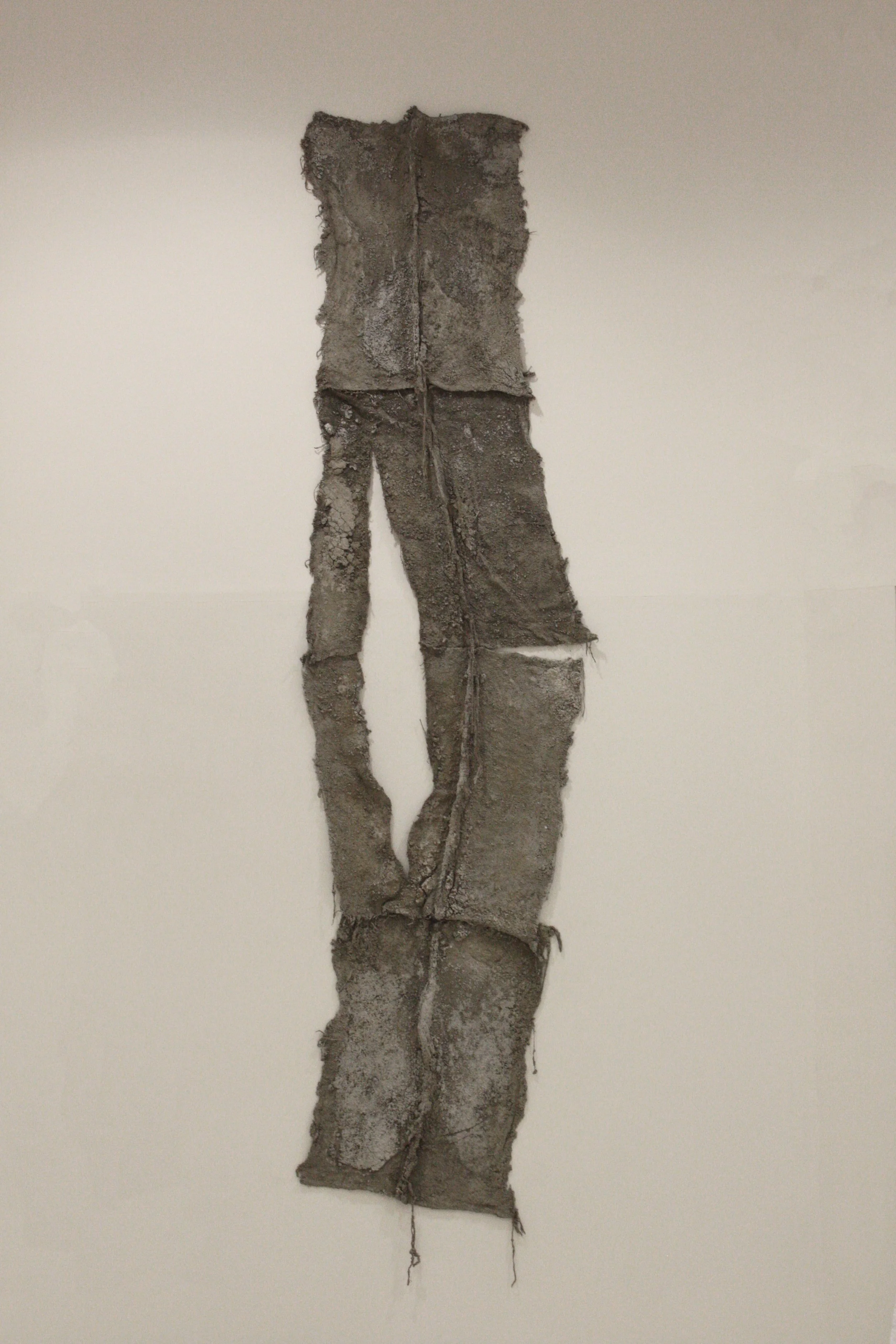

Nailed to the walls, a series of abstract animal hides in concrete take form. Worn and weathered, the backs are made to crumble; they are formed through their erosion. Concrete remnants are collected, crushed, and used again to create new spines. Each version of the back carries a part of what came before - never truly lost; the material remains, returning anew. It comes back to ideas of personhood and discovery, but also to the simultaneity of discovery and loss. The spines, formed from previous versions, are at once past selves and present realities—held together by what remains.

The hides become relics of the body, removed from the whole. They suggest notions of self-awareness alongside a more existential form of self-questioning. How do we stand? How do we navigate?

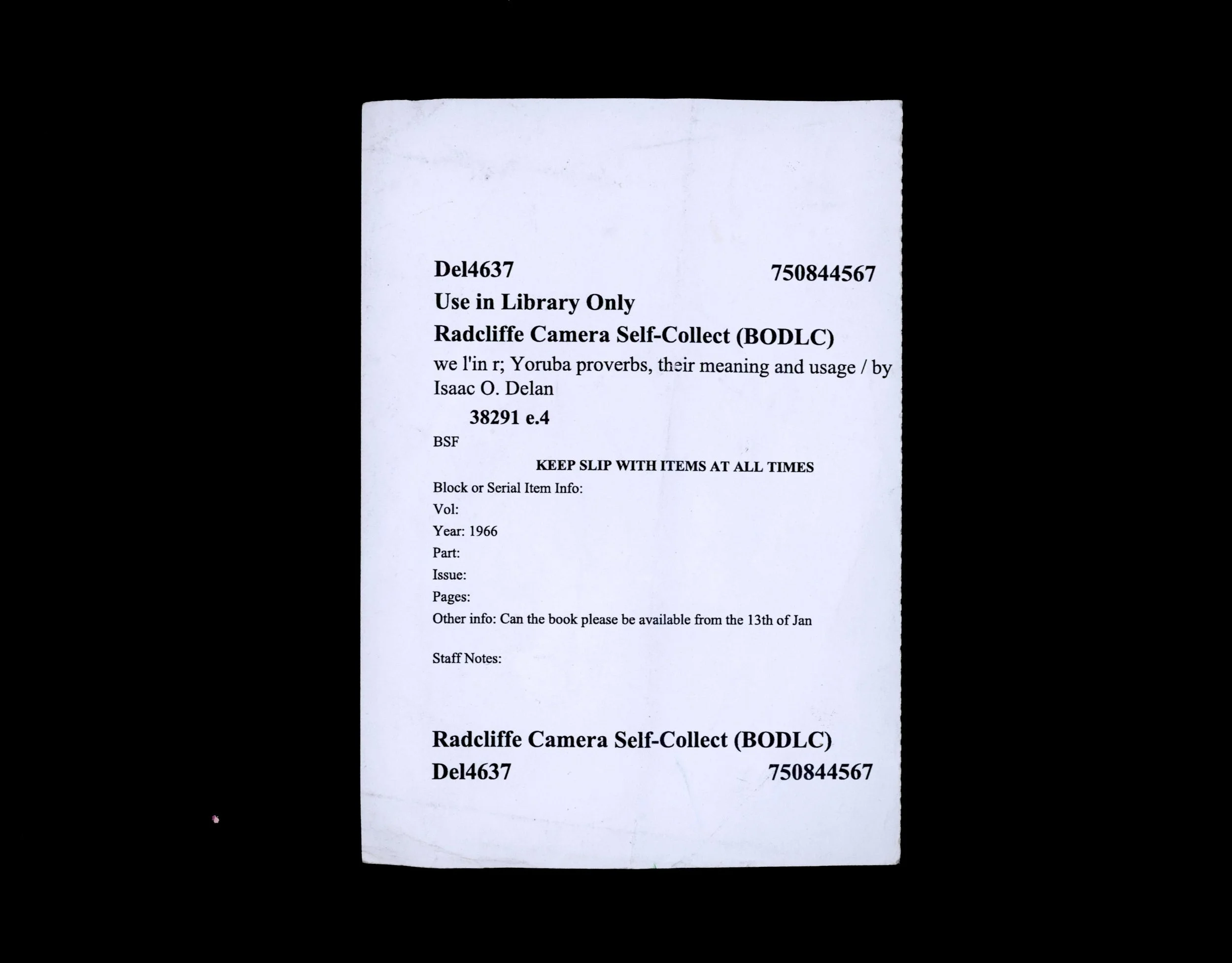

A chance encounter - A library slip from the University of Oxford depicts the borrowing of her great-grandfather’s book Òwe l’ẹşin ọrọ; Yoruba proverbs, their meaning and usage — during her studies there. The value of proverbs is epitomised in this Yoruba proverb:’Òwe l’ẹşin ọrọ; bi ọrọ ba nu, owe ni a fi nwa a’, meaning: ‘a proverb is a horse which can carry you swiftly to the discovery of ideas sought’. There is a proverbial nature to the works, they use this language of nonlinear storytelling to perhaps open ways to consider our relationship to land.

The ‘meeting’ of her great-grandfather, not in Nigeria but searching through the archives of Oxford University, asks further questions of ownership - who tells our stories, who owns knowledge, and who owns Nigeria? Furthermore, how do we navigate institutions in which our histories have been overlooked? Ultimately, the book remains elsewhere, its authority bound - the slip a totem calling out to them.

The series of catalogues presented draws the viewer back to the specificities of such questions, and suggests that these questions have persisted for many years - how do we record the history of the land of Nigeria and its many conceptions of familiarity? How were artists, writers, directors, and architects trying to make it familiar, and how has it already been made familiar? The cows remind us that even in the familiar there can be vast voids of the unconscious. Without knowing, we are kept wandering through the desert, grazing endlessly at questions that cannot be answered but must be explored.

Time moves between the works, suggesting present, a past, a possible future. The library slip a past that continues and endures. The cows are an ungoing present. While the concrete hides cannot be located in a specific time, it is neither before or after as a form. Throughout the show, Delano assures us that aimless grazing and directionless navigation is an essential part of being. Questioning our location, both physically and metaphysically is so instinctive an act that we see ourselves reflected in the cows of Northern Nigeria. We feel the power of their contorting backs as they trudge endlessly through their landscape, both knowing and unknowing.